Samuel Aranda, World Press Photo of 2011

The World Press Photo of 2011 has been awarded to Samuel Aranda from Spain. His striking photograph produced for The New York Times shows a woman holding a wounded relative during protests against Yemen President Ali Abdullah Saleh in Sanaa on Oct. 15. Similar to past winners of the World Press Photo award, arguably the most important professional distinction for photojournalists, the image is highly charged, dramatic and evocative of a painful event. It is, at first sight, an image that is easily understood precisely because it alludes to feelings and emotions that are universal: the physical pain endured through injury, the emotional pain endured through a relatives injury, and, in extreme, the traumatic pain endured through death. Apart from this schema that can be attributed to a whole range of photojournalistic images, in this blog post I wish to dig deeper, and discover why particularly Aranda’s image was chosen.

The power of the photograph is partially based on its simplicity. The viewer is confronted with two figures embracing each other. The fact that the male figure is half naked and the female figure fully veiled further alludes to a binary construction: male and female, naked and veiled, dirty and clean, wounded and unwounded, and finally, vulnerable and protecting. Importantly, neither the man’s nor the woman’s face are visible which adds ambiguity to the image. Yet the subjects’ anonymity also allows the viewer to glance at a moment of intense pain and grief. If the man’s and woman’s face were visible, the photograph would have been too intrusive, too invasive, too exploitative. In other words, the very anonymity of the embracing figures distinguishes this photograph from others.

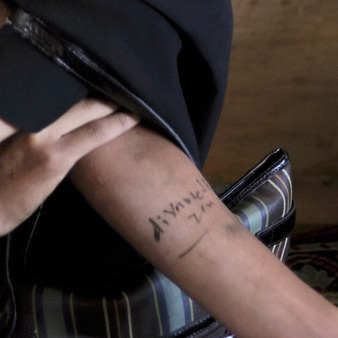

A number of intriguing details in the photograph add to a increasingly complex narrative. The background of the photograph appears to show a simple piece of wood suggesting the subjects are in a make shift shelter. The man, whose wounds are not actually in the frame of the photograph, has a code written on his forearm. The man is thus marked in more than one way: by the wounds he has inflicted and by the pen that presumably gives the doctors and nurses an indication of these wounds. I cannot help but wonder what the quickly scribbled code on the man’s arm might refer to? How severe is his condition? In part, I am asking myself these questions because his wounds are not visible in the photograph. Again, comparable to the subjects’ anonymity, the very invisibility of the source of pain heightens the dramatic effect of the image. The veiled woman meanwhile, we assume, is able to see and understand the severity of the man’s pain while she seeks to comfort him.

There is, of course, also a religious dimension to this image. The photograph was taken in Yemen in the wake of the so-called Arab Spring. Unlike comparably secular countries of Northern Africa, namely Tunisia, Libya and Egypt, the full veil signifies the extent of islamist rule in Yemen. In fact, only ten days after Samuel Aranda took above photograph, a number of women burnt their veils on the street of Sanaa, the Yemeni capital, in defiance of President Saleh. Yet, in spite of the strong islamist connotations of the full veil, I cannot help but be reminded of the Christian iconography of the Pieta in which the Virgin Mary holds the body of Jesus after his death. While the subject of the photograph is taken within the context of an islamic culture, it should be remembered that the photographer, who framed this context, is of Spanish descent and therefore, culturally speaking, informed by the iconography of the Catholic church.

Giovanni Bellini, Pieta (detail)

Close up of Michelangelo’s Pieta vs. close up of Samuel Aranda’s photograph

A close up of Michelangelo’s sculpture of the Pieta illustrates the many similarities to Aranda’s photograph: the downward gaze of the woman, the slightly tilted position of her head, the low vantage point of the viewer who is invited to emphasize with the subject’s pain, and of course the veil itself. Rather than crudely superimposing the iconography of one religion on top of a culturally complex event, I believe that Aranda’s photograph encapsulates deep felt human emotions that have no religious, cultural or geographic boundaries. It is an image that can easily be read as one person feeling pain, while another tries to give comfort. The photograph is a powerful symbol for the dramatic shift in the Arab world in which some elect to fight, in spite of death, so that others can be free.

For more on this topic, please read Susan Sontag’s Regarding the Pain of Others and Susie Linfield’s The Cruel Radiance: Photography and Political Violence. Other recommendations can be found in our online bookshop.